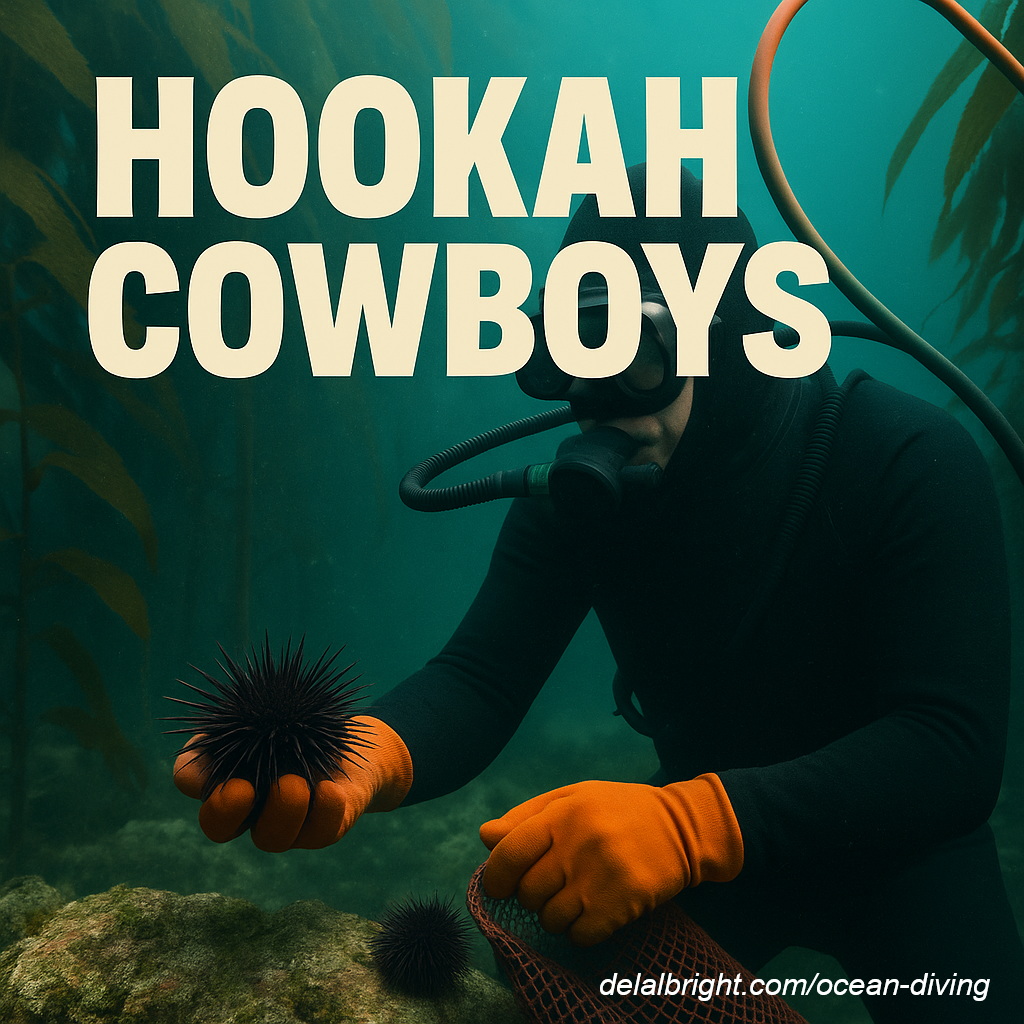

The Hookah Cowboys: Inside California’s Wild Era of Commercial Urchin & Abalone Divers

By Del Albright

Before the abalone closure, before kelp collapse, before purple urchin barrens — California’s coast saw a different kind of tide. It belonged to the commercial abalone and urchin divers of the 1970s and 1980s.

Armed with hookah compressor rigs, long dive hoses, and a “gold-rush” attitude, these divers chased shellfish for processors and export markets in a world that looked more like maritime outlaw lore than a tidy modern fishery.

This page captures that history — the gear, the culture, the risks, the money — and the strange frontier that once existed beneath the kelp canopy. I’ve done my due diligence in researching this (with AI help), as well as living in Ft. Bragg during the era.

Where It Began: A Shift in the Fishery

As legal abalone harvests declined and international demand for uni (sea urchin roe) surged, commercial divers shifted to a new target.

By the mid-1970s:

Japanese buyers were on the docks

processors were offering contracts

urchins became a viable alternative catch

Many of the first commercial urchin divers were former abalone specialists — guys already comfortable with deep work, cold water, and living paycheck-to-catch.

The Hookah System

Unlike recreational tank diving, commercial crews used surface-supplied air, pumped by a diesel or gasoline compressor on deck.

The divers:

followed a long hose down into the kelp beds

stayed underwater for multiple hours at a time

worked the reef by hand

hauled urchins or abalone into mesh baskets and ascending bags

The only lifeline was a humming hose tied back to the compressor.

If the motor coughed… so did the diver.

Grit, Danger, and “Bottom Time”

Stories from the era include:

four-hour bottom sessions

freezing North Coast surge

entanglement in kelp

deep-decompression hangs

pushing Navy dive tables

compressor failures

territorial skirmishes over prime kelp lanes

Some divers hung on oxygen hoses in the dark at 15 feet, waiting out decompression.

Others chased deeper grounds at 150 to 200 feet — a level of underwater risk that’s almost hard to comprehend today.

One diver famously described the deep-crew crowd as “really nuts — a different breed entirely.” I spent a few evenings in local bars with some of these divers and I can attest to their “different-ness.” (smile)

It wasn’t a hobby. It was a profession on the edge.

The Money Game

Early reports say some urchin buyers wanted to pay as much as 25 cents per pound.

Processors allegedly negotiated that down to just a few pennies to keep divers harvesting abalone, too.

As exports to Japan grew, so did the stakes:

better compressors

improved rakes and bags

specialized boats

crews that worked the tides like prospectors

For a while, the urchin fishery was a genuine ocean gold rush.

The Culture: Long Hair, Long Hoses, and Saltwater Grit

Accounts from the era describe:

sunburned boat decks

nights in small ports

competition for the best coves

rival crews on the same reef

camaraderie mixed with risk

One memoir compared the early diver scene to “pirates with compressors” — hard-driving ocean workers chasing a living below the kelp canopy. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was unforgettable.

Were They the Villains? No. But the Era Matters.

It’s important to draw a fair line:

These were commercial divers operating under commercial licenses. They weren’t the recreational over-limit crowd later found with gunny sacks full of abalone.

The Hookah Cowboys lived in a different world:

working quotas

supplying processors

chasing market demand

Their story is part of the larger arc of California’s coastal harvest history — one that later collided with ecosystem decline, modern science, and today’s abalone closure.

They weren’t responsible for kelp collapse, sea star die-offs, marine heat waves, and the ecological failures that came decades later.

But their era shows how intensely humans once worked the reefs, and how resource opportunity shifts as species rise and fall.

Legacy and Perspective

When divers talk about those days now, they do so with mixed feelings:

pride in the skill

memory of the danger

respect for the ocean

awareness that the world, and the fishery, has changed

The Hookah Cowboys were part of a very specific moment in California history — when the sea was still rich, the kelp was thick, and nobody yet saw the collapse that would come.