California’s Red Abalone Closure: What Led to It, What It Means, and How the Future Looks

By Del Albright

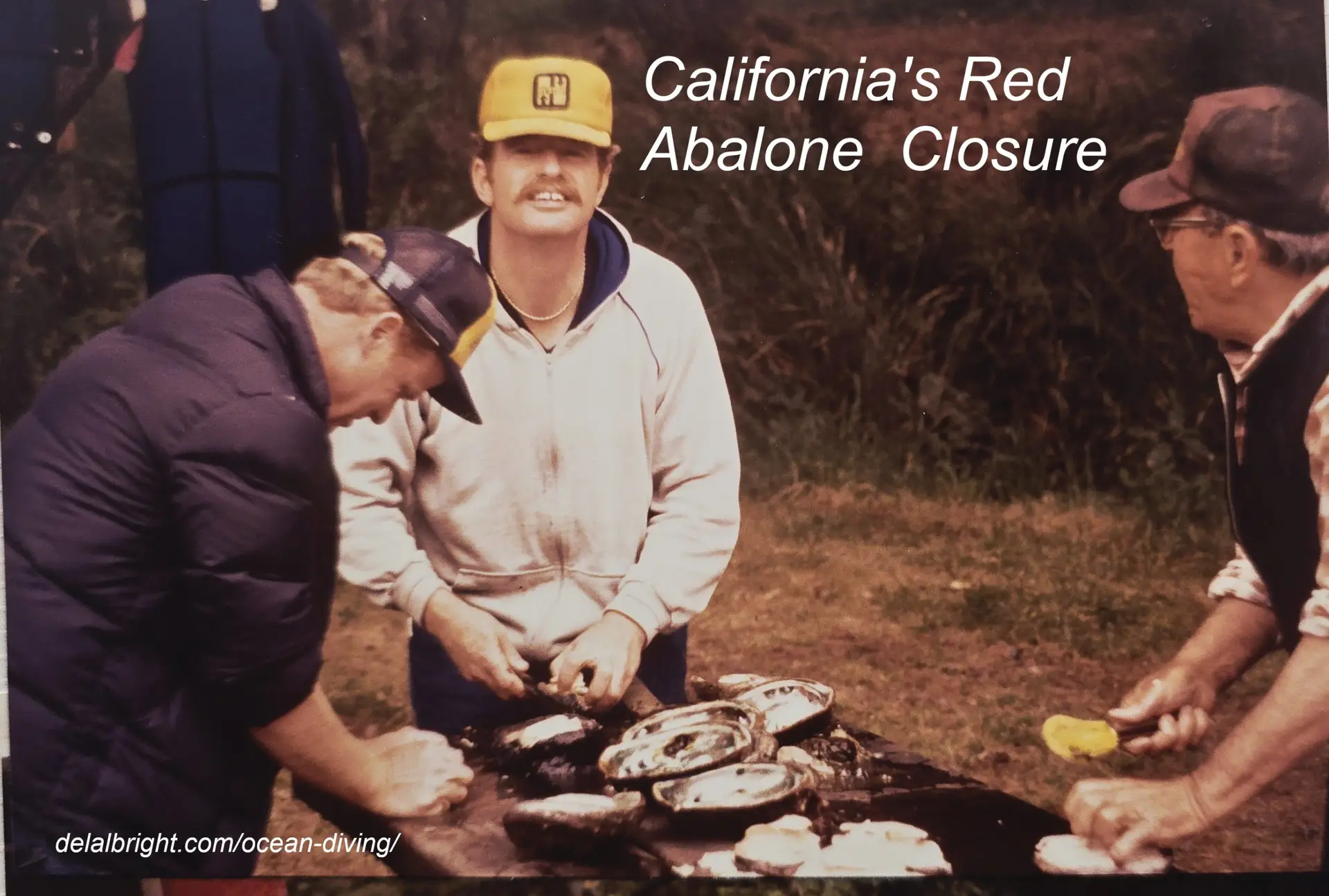

For decades, red abalone diving along California’s North Coast was part sport, part heritage, and part coastal economy. Early-morning tides, icy Pacific swells, and the scrape of iron bars against rock — those memories are etched into the lives of thousands who worked the coves, camped on the bluffs, and came home to family cookouts with fresh abalone steaks.

My family, friends, and I were part of that tradition for decades, from the 1970s through the 2000s. I lived in Fort Bragg for much of that period, and even after moving away for work, I returned frequently. We lived the ocean life. We operated out of Noyo Harbor and Albion for hundreds of dives — abalone diving, spearfishing, crabbing, and rock fishing. In the early years we used inner tubes and inflatable rafts, eventually graduating to Boston Whaler boats. And we always obeyed the law, taking only our limits. Back then, in the 1970s, that limit was five abalone — no tags required. It was an amazing era to be a diver on the Mendocino Coast.

But that era came to a halt in 2018, when the State closed the last remaining recreational red abalone fishery. The decision followed years of ecological decline, scientific warnings, and a mounting list of enforcement challenges. What began as a temporary emergency closure has since become a long-term moratorium — one that may now extend through 2036.

This page lays out the history that led to the closure, the science beneath it, the human role in the decline, and what ongoing restoration efforts may make possible in the future. I’ve done due diligence (with some AI help) in digging up the facts as best I could.

A Perfect Storm Beneath the Surface

The closure wasn’t triggered by a single factor. It was the result of several interwoven ecological collapses:

Bull Kelp Failure

California’s northern kelp forests suffered steep declines after prolonged ocean warming and marine heatwaves. Without dense kelp canopy, abalone lost their primary food source.

Sea Star Die-Off

Sea stars — natural predators of purple urchins — were nearly wiped out by disease. Without them, urchin populations multiplied unchecked.

Urchin Explosion & “Urchin Barrens”

Massive numbers of purple urchins turned once-thriving kelp beds into barren rock, stripping remaining kelp from the reefs. These “barrens” created starvation conditions for abalone and many other species.

Biological Surveys Confirmed Collapse

Population assessments along the Sonoma–Mendocino coast showed abalone densities well below the recovery thresholds set by state management plans. Declining size-class distributions and weak juvenile recruitment signaled long-term trouble even if harvest had continued legally.

Human Pressure: Overharvest, Limit Violations, and Enforcement History

Long before the official closure, wardens and biologists were documenting a pattern that didn’t help the situation.

Coast-side checkpoints regularly found gunny sacks of abalone far above the legal limit. Vehicles were stopped with dozens of abs hidden under seats or ice chests. Some divers poached for the black market; others simply ignored the regulations completely. In the 1980s (and before), I heard rumors among local divers that the “black market” of San Francisco Bay Area restaurants would pay $100/ab. Whether true or not, poaching and over-limits were common from what I witnessed. And yes, I turned in poachers and outlaws when I could.

There was another common practice in the old days where a diver in wet suit would just float along, hold the inner tube, and act like he was diving while his buddies collected abs for all “divers” present. The “floater” or “deadhead” was not a diver; just an actor. The group might have stayed within legal limits, but Fish & Game definitely issued tickets for obvious deadhead type divers. This may not have contributed to the overall decline of the ab population, but it goes to show what folks will do to push the limits with something they really want.

The problem wasn’t a “few bad apples” — it was significant enough that enforcement staffs regularly flagged it as a stress factor when the species was already under strain.

The over-limit era is part of the uncomfortable truth:

While environmental forces drove the collapse, illegal take and disregard for limits contributed to the downward spiral and eroded confidence that reduced harvesting rules alone could protect the species.

Regulatory Action and the Official Closure

In late 2017, the California Fish & Game Commission — relying on scientific data from the Department of Fish & Wildlife — voted to close the recreational abalone fishery.

The ban took effect in early 2018 with the intent of being temporary.

But subsequent ecosystem surveys showed:

kelp forests struggling

urchin densities still extremely high

abalone recruitment weak or absent

population densities far below recovery criteria

Because recovery hasn’t materialized, the State has extended the closure multiple times. Current policy considerations look toward April 1, 2036 as the next potential landmark date.

The goal isn’t punishment or loss of tradition; they say it’s population survival.

Lost Commerce, Lost Tradition

The closure didn’t only remove abalone from the rocks.

It removed:

lodging revenue

dive-shop business

restaurant traffic

fuel sales

seasonal tourism income

gear suppliers

guide operations

For coastal towns, abalone season was a dependable economic pulse. Without it, some businesses closed. One of the most storied dive shops on the Sonoma–Mendocino coast shut its doors indefinitely shortly after the closure. We said goodbye to Sub Surface Progression, THE dive shop of the north coast.

Families also lost something intangible. The opener weekends, campfires, and ocean-to-table feasts became history.

Looking Ahead: Restoration, Research, and Hope

Though current data suggests abalone are not yet ready for harvest, restoration efforts are underway:

kelp-re-seed and out-planting projects

experimental urchin removal sites

long-term ecosystem monitoring

partnerships between universities, conservation groups, and divers

Some coves are showing tentative kelp resurgence. Divers have reported small signs of abalone stability in isolated pockets. But the system is still fragile.

Abalone are slow to grow and slow to reproduce. Even under ideal conditions, recovery is measured in decades.

The closure gives them time — and buys us a chance to fix the ecosystem beneath them. There is a lot to this.

Stewardship Going Forward

As lovers of the outdoors and ab diving, we should look at this closure as a conservation mission that needs our help if we are to get back this diving tradition. We can “throw rocks” at the system, or be part of the solution.

It invites us to:

advocate for kelp-forest restoration

support research

respect closures and limits

combat poaching

stay informed on the science

Someday, abalone may again be part of our coastal heritage. I sure hope so.

If they return, let it be to a restored coastline, balanced ecosystems, and sustainable harvest rooted in stewardship.

Until then, we wait — patiently — and responsibly – and we help where we can.

— Del Albright

If you have memories of abalone diving, I invite you to share them.

Photos, stories, dive logs, recipes — these are worth preserving until the fishery is ready for us again.

And if you care about California’s coast, support the restoration.

Because the future of the red abalone is ultimately a reflection of the future of our ocean.

— Del Albright